Standardization and Personalized Learning

Teachers and leaders in the schools I have studied balanced the need for standardization/learning standards with students need for autonomy and agency and desire to pursue interest-based learning targets. Standards-based learning does not have to negate designs for student agency and interests. When standards are unwrapped and deeply understood by educators, they can work with students and families to participate in co-creating with teachers their personal instructional designs to gain and demonstrate mastery over standards.

France, P. E. (2017). Is Standardization the Answer to Personalization? Educational Leadership, 74(6), 40–44.

In reviewing the work of the Saint Paul Public Schools Office of Teaching and Learning I ran into three familiar terms: unwrapping, sequencing, and progress monitoring. In so doing standards and personalization were drawn closer together. For more on the complementary roles of standards and personalization in reducing inequity and achievement gaps, see Paul France’s recent article in Educational Leadership. (1)

Unwrapping [Unpacking] Standards

Nouns : verbs content : skills; know : do

Unwrapping standards is a process of close reading and deconstructing learning standards to gain a deep understanding of the knowledge and skills called for in the standards.

Contemporary standards are written to describe what students should be able to know and do at a particular time, not define how they will arrive at these ends. Educators unpack standards as part of the instructional design process by close reading the standards, paying particular attention to verbs and nouns to understand the knowledge and skills learners are to acquire. Educators then then design learning experiences, tools, tasks, routines, and assessments to develop and assess students’ knowledge and skills as they relate to each standard. Many standards are written using the language of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, calling for students perform high-level learning tasks. (2)

Why is this important?

Even the best and most thoughtful standards alone can not change teaching and learning practice. (3) Educators change teaching and learning practice. With a deep understanding of well-written education standards and routines to support instructional design, teachers can create experiences for learners that guide them to achieve standards, to perform and address questions at high levels. Unwrapping standards is also essential in the differentiation process. With a deep understanding of the essential knowledge and skills students need, teachers can work with students to design learning experiences at their level to gain and demonstrate mastery over the standard. (4)

A critical note.

Standards are agnostic to students’ interests, passions, and backgrounds. Engaging students’ interests, backgrounds, and developing need for autonomy are essential intrinsic motivators that lead to engagement (5). They are agnostic to the diverse funds of knowledge students bring to the learning ecosystem. Teachers would be wise to engage students and families in participatory pedagogies, to consider new literacies and emerging designs for learning when unwrapping standards, creating the curriculum (content), and considering their pedagogy (designing for learning). (6)(7)(8) Standards are a starting point – a minimum. Thinking fo them as anything else leads to inequitable outcomes. (9) See my related post for more on the history of standards in the united states.

Sequencing [Chunking, Pacing] Content

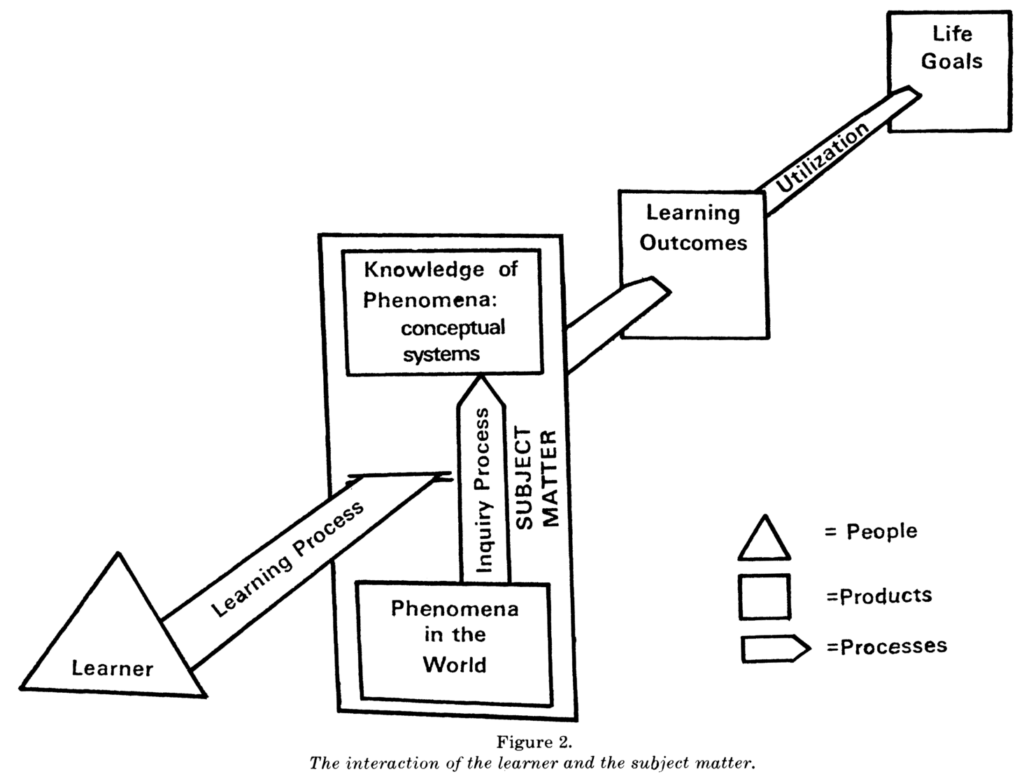

Sequencing, chunking, and pacing content relate to how educators order and structure learning opportunities. At a classroom level, sequencing looks like an ordered list of knowledge and skills paired with lesson plans or personalized learning plans to develop students’ knowledge and skills over time to achieve learning targets. For more on sequencing, see Posner and Strike’s (1976) seminal article on the matter. (10) The main takeaway for me in their work is that sequencing should be considered from the learners’ point of view and as an interaction between learner and subject matter [content] that stresses the utilization of subject matter to achieve personal life goals. Again, this can align with personalized learning, where students and parents participate in the instructional design process to achieve mastery over standards and life goals.

Progress Monitoring

Progress monitoring is a process of assessing student learning. I and others argue that simply monitoring progress is not enough. Progress assessments need to be part of a formative feedback system with routines in place to utilize progress information to change and continually improve teaching and learning practice. (11)(12) In personalized learning, monitoring progress happens at the level of each individual student. Students and teacher collaborate to collect and analyze data on their progress over student-, interest-, and standards-based learning goals. With this knowledge in hand, they design or revise their learning plan based on the standards. In this way, the formative feedback system closes the loop between standards, sequencing, and progress monitoring.

References

(1) France, P. E. (2017). Is Standardization the Answer to Personalization? Educational Leadership, 74(6), 40–44.

(2) Bloom, B. S. and Krathwohl, D. R. (1956) Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals by a committee of college and university examiners, New York, Longman.

Bloom’s taxonomy is a way to understand the rigor or level of a question or task. High-level tasks ask learners to analyze, synthesize, and apply knowledge and skills in creative ways while low-level tasks ask learners to understand concepts and memorize facts. Search Pinterest for inspiration and connect with others who share your interests.

(3) Tarman, B., & Kuran, B. (2015). Examination of the Cognitive Level of Questions in Social Studies Textbooks and the Views of Teachers Based on Bloom’s Taxonomy. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 15(1), 213–222.

Tarman and Kuran found that – even in school systems with strong standards in place – in practice, teachers and students can still often rely on inherited artifacts such as textbooks to drive their practice and thus be asking and addressing low-level questions as described by Bloom’s Taxonomy.

(4) Morgan, J. J., Brown, N. B., Hsiao, Y., Howerter, C., Juniel, P., Sedano, L., & Castillo, W. L. (2013). Unwrapping Academic Standards to Increase the Achievement of Students With Disabilities. Intervention in School and Clinic, 49(3).

Morgan et. al describe an intervention in which teachers use graphic organizers to unwrap and understand standards and create differentiated learning designs for students to ensure achievement and growth for all students.

(5) Christenson, S. L., & Reschly, A. L. (2012). Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. (S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie, Eds.). New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7

(6) Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., Gonzalez, N., & Moll, L. C. (1992). Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms. Theory Into Practice, 31(2), 132–141.

(7) Ito, M., Gutiérrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., … Watkins, C. S. (2013). Connected Learning. Irving. Retrieved from http://dmlhub.net/publications

(8) Halverson, R., Barnicle, A., Hackett, S., Rawat, T., Rutledge, J., Kallio, J., … Mertes, J. (2015). Personalization in Practice: Observations from the field (No. 2015–8). WCER Working Paper. Madison.

(9) Lee, J. (2004). Multiple Facets of Inequity in Racial and Ethnic Achievement Gaps. Peabody Journal, 79(2), 51–73.

(10) Posner, G. J., & Strike, K. A. (1976). A Categorization Scheme for Principles of Sequencing Content. Review of Educational Research, 46(4), 665–690.

(11) Quenemoen, R., Thurlow, M., Moen, R., Thompson, S., & Morse, A. B. (2004). Progress Monitoring in an Inclusive Standards-based Assessment and Accountability System (Synthesis Report No. 53). Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota, Natinoal Center on Educatinoal Outcomes.

(12) Halverson, R. (2010). School Formative Feedback Systems. Peabody Journal of Education, 85(2).